Louisville Magazine is Louisville's city magazine, covering Louisville people, lifestyles, politics, sports, restaurants, entertainment and homes. Includes a monthly calendar of events.

Issue link: https://loumag.epubxp.com/i/267865

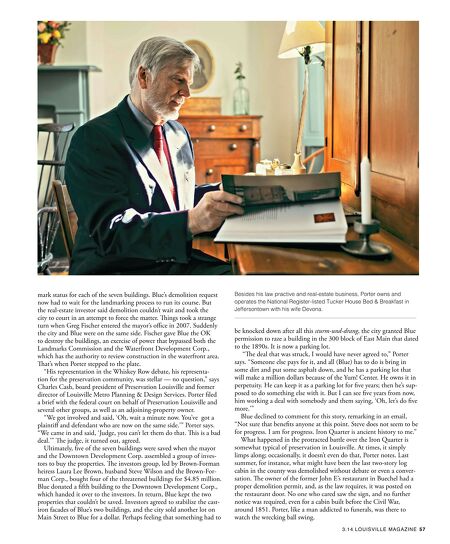

5 6 LOUISVILLE MAGAZINE 3.14 fnd are the symbols of clear success — we win, the other guy loses. Anyone can have an ideology; solutions carry their own rationale. Vic- tory takes money. Porter sits in the front parlor of one of his victories, the 1840 bed- and-breakfast he and his wife Devona bought and remodeled with historical fealty in 1999. He wears moccasins without socks, a dark sweater and khakis. Seventy years old and 6-foot-2-inches tall, he perches on an antique loveseat unafected by the parlor's sharp chill or the daintiness of the seating. Te brick home sits on narrow, winding Tucker Station Road, which is still a pretty country lane. Porter is de- termined to keep it so, despite plans for a 300,000-square-foot FedEx distribution center across the road and several hundred yards away. Te FedEx plans include more than 1,000 parking spaces — 400 of them for tractor-trailers — and 600 employees working round the clock. Two other large distribution centers are proposed nearby. Porter is digging in for a fght — or more aptly, the compromises he hopes a good fght will bring. He can't hope to stop development. "We know it's going to happen. It's already zoned for it," Porter says. But he intends to push compa- nies to keep lights from the windows of nearby homes, noise from nearby bedrooms, diesel exhaust from nearby lungs, and tractor-trail- ers from Tucker Station Road. "Tey're going to have to build me the biggest sound wall anyone's ever built," Porter says. "It's not to stop the development. It's not to stop these 500 jobs or anything else. It's to make FedEx do it right." "I don't win many wars," he says. "I win a lot of battles. Developers pretty much get their way." Given the industry heading toward his neighborhood, maybe it's a little premature to call his homestead a victory. "Maybe he shouldn't have bought a home in the middle of an industrial site," attorney Bill Bardenwerper says. "It was zoned single-family residential when we moved here," Porter says later in response to Bardenwerper's comment. If Porter has a nemesis, land-use attorney Bardenwerper of Barden- werper, Talbott & Roberts, is that man. Te two square of on neigh- borhood issues and preservation battles. Tey're about to duke it out on FedEx, just the next chapter in their long history as frenemies. But lawyers will be lawyers, and both are quick to count the other's virtues before they point out the fatal faw. "I consider him a friend," Porter says. "First of all, he's brilliant. He's spent most of his career working in the area of land use, so he knows the law. He knows the regulations. Put together a brilliant mind with vast experience, and you've got a very successful person." Bardenwerper makes a similar avowal: "I've known (Porter) forever and I call him a friend. When an opponent shows up at my father's funeral, I appreciate that. . . . My clients will probably get mad at me for saying anything nice, but he's got a good personality. He's warm. He represents his clients well. . . . And he can sometimes ask for too much. "Oftentimes he doesn't know when to stop," Bardenwerper says. "It's just one more thing, one more thing, one more thing. And you come up with a plan and he continues to oppose it." Porter has his own critique: "Bill's theory is, Jeferson County should be paved." Ten there's historical preservation. Last year, after a long fght, Bardenwerper won permission for the Bauer family to demolish the Brownsboro Road building that once housed Bauer's 1870 restaurant and later the restaurants Azalea and La Paloma. Bardenwerper still sounds frustrated over the skirmishes that started in 2008 when the Bauer family applied to raze the dilapidated restaurant and put in a Rite Aid drugstore. Te core of the Greek Revival-style building dated back to around 1868, but the place was a wreck, held together by little more than its aluminum cladding, Bardenwerper says. In fact, when part of the siding was removed, the structure sagged in exhaustion. Te basement was a murky swimming pool — the result of two fres and subsequent frefghting — and mold draped it like tattered cur- tains. "Tat stuf was every color known to man," Bardenwerper says. "I think I coughed for a month after seeing it." Porter represented the city of Rolling Hills in early discussions about the Bauer property. "Steve Porter and the historic-preservation people acted like the Knights Templar protecting the Holy Grail," Bardenwerper says. "But 99 percent of the residents didn't give a damn about that rotted old building except for the memories they had." Bardenwerper maintains the fuss about preservation was cover for the neighborhood's real objection: Tey didn't want a Rite Aid on the property. Still, public hearings on the building's fate attracted hundreds who argued the structure's historic value, and they signed petitions asking that it be declared a landmark by the metro government Landmarks Commission. Once a property is designated a landmark, its owners must prove economic hardship before demolition can be considered. By the time the Bauer family was able to prove hardship, Porter was no longer part of the case. But he sounds like he may have swallowed the building demolition — or at least some demolition — without too much of a fght. "Te Bauer's property is probably a good example of a building in which parts of it, without question, should be torn down," Porter says. But it was never a slam-dunk, not with strong feelings about the prop- erty's importance. "You have to go through the process for a determi- nation to be made about what's valuable and what's not," he says. It's often hard to see that anyone wins in preservation fghts, and in the Bauers property tussle particularly. Preservationists lost the build- ing. Te Bauers lost Rite Aid, which wandered away during discus- sions, and other plans for the property have not come to fruition. Indeed, many preservation fghts end in unhappy compromise. Most notable may be the agreement that saved Whiskey Row (aka the Iron Quarter), a group of historic buildings on the north side of West Main Street's 100 block. Te compromise put a stop to building owner Todd Blue's plans to raze the structures, but in exchange Blue was allowed to demolish a building a few blocks away — a possibility not previously on the table or discussed publicly. Blue and Cobalt Ventures had purchased seven Whiskey Row build- ings in 2007 for $4.3 million. When he bought them, the buildings had been vacant for at least 20 years, and Blue made no improve- ments. Tree years later, not long after Blue rebufed then-Mayor Jerry Abramson's eforts to bring another developer in to buy the build- ings from Blue, the owner fled for an emergency demolition permit for Whiskey Row. His contention? Te buildings were in imminent danger of collapse. Constructed mostly between 1857 and 1877, the Whiskey Row buildings were prized for their age and design. Tey are the work of prominent Louisville architects — including Henry Whitestone, D.X. Murphy and John Andrewartha — and represent an important era in the city's history of distilling and warehousing. Fur- ther, they are valued for their cast-iron facades. Reportedly, Louisville is second to New York City alone in its number of cast-iron buildings. With demolition an imminent threat, preservationists sprang into action and rounded up more than 1,000 signatures to fle for land- "I don't win many wars," Porter says. "I win a lot of battles. Developers pretty much get their way." 54-59 PORTER.indd 56 2/19/14 9:46 AM