Louisville Magazine is Louisville's city magazine, covering Louisville people, lifestyles, politics, sports, restaurants, entertainment and homes. Includes a monthly calendar of events.

Issue link: https://loumag.epubxp.com/i/144820

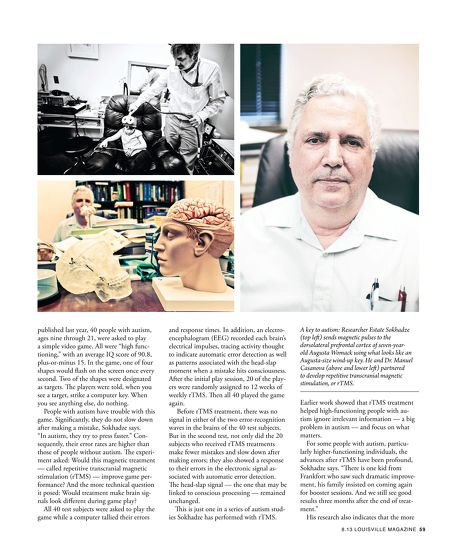

but she wouldn't repeat it," her dad, Rob, says. "Moe would say, 'Tat counts as your frst word.' I would say, 'Tat doesn't count as her frst word. She won't say it again.'" Sometimes she grunted. Sometimes she growled when some child crowded too close. She'd even slip in lines from her favorite movie, Madagascar. She sang her ABCs. She knew every magnetic letter on the refrigerator door. But she wouldn't have a conversation, wouldn't speak in sentences, wouldn't communicate. And she would echo. "Do you want something to drink?" Moe would ask. "Do you want something to drink?" Au58 LOUISVILLE MAGAZINE 8.13 gusta would respond. "No, I'm asking you." "No, I'm asking you." P eople tell you, 'You should just love her for who she is. Don't worry about it,'" Rob says. "Don't worry about it? What are you talking about? What do you mean, don't worry about your kid?" Tere are simply too many things to worry about. Augusta would wander of. She hated the feeling of clothing on her skin — she still does — and would take her clothes of whenever she could, winter or summer. She had uncontrollable tantrums. Moe fghts to maintain her composure. " "I'll try not to cry," she says, "but I'm telling you, it's like a train wreck when it happens to you. Your kid goes outside; she's putting dirt in her hair; she's sitting in a sandbox naked — the weirdest stuf happens." Tere's a video on YouTube of a little girl in a princess dress spinning and spinning and spinning, long past the point when even her viewers are dizzy. Te mother's comment says the girl is "stimming," as in "stimulating" herself. Some children fap their arms to stim. Some walk on their toes. Some bang their heads. It may be a way to control all the incoming stimuli. "It's inherent to the diagnosis," Tomcheck says. Many children with autism like to squeeze into tiny spaces for the same reason. Moe has a video of Augusta in a clothing hamper, watching a movie. "If she has a meltdown," Moe says, "I'll fnd her in her room behind her bed, or under all of my pillows, because it's tight, and it squeezes." Tere's something about the swaddling embrace of inanimate objects that keeps chaos in check, controls all the things coming at her, corrals all the stimulation. Autism, it often appears, is all about stimulation: limiting it, inducing it, tamping it down, taming it. And stimulation is also Tato Sokhadze's aim as he holds an electromagnet to Augusta's head, slightly left of the center of her skull. Over the course of the next few minutes, he'll direct about 100 low-frequency electromagnetic pulses to a part of the brain called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. In previous experimental sessions, he treated the same cortical structure on the other side of her head. Augusta sits quietly. Te magnet looks like the key to a human-size windup toy. With each eye-blink-long electromagnetic pulse, the magnet clicks audibly. Te dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is part of the brain's executive suite. Its domain is vast, making critical contributions to things like applying mathematical rules and crunching if-then statements. Here is where you adopt the perspective of another person, or analyze memories, or perform costbeneft analyses. From this brain address comes the ability to rein in your emotions. Tis is also where you note and correct your mistakes. In several previous studies Sokhadze found that regular application of magnetic pulses to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex not only changed how the brain behaved, but improved experimental subjects' performance on some tasks as well. In a study