Louisville Magazine is Louisville's city magazine, covering Louisville people, lifestyles, politics, sports, restaurants, entertainment and homes. Includes a monthly calendar of events.

Issue link: https://loumag.epubxp.com/i/144820

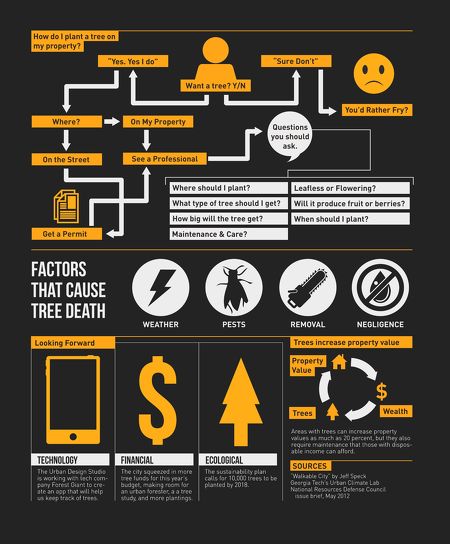

Continued from page 46 climbing champion. Our frst meeting is at Ramsi's Cafe on the World, where, for the frst hour, we do nothing but sip water and talk trees. "We have a municipal, which takes care of city trees," he says. "Ten we have the park system, which is sort of municipal but is very clearly defned with what they manage (Olmsted parkways and city parks). Ten we have the private sector. And the private sector is not regulated at all. It's the Wild West." Because lack of responsibility can lead to tree neglect, O'Bryan says he would love to see regulation in his industry. "I'm in ornamental trees and shrub services," he says. "It has an SIC (standard industrial classifcation) code, 0783; it has a defnition. My company fles its taxes. In the private industry for tree work right now, the majority of work being done in this community is in the black market. Tat means it's not taxed; it's performed by companies that pay their workers under the table." O'Bryan tells me that inexperienced workers, with the approval of ill-informed residents, remove many trees in the city, often unnecessarily. "Te current city arborist doesn't have the authority to manage that and he doesn't have the resources," he says. "What we need is an urban forester who can take a big vision, something general and vague and say, 'What do we want this city to look like in 20 years? Do we want to be a city of trees or do we want to live in a desert? If you go to Greenville, S.C., or Charlotte, N.C., it is amazing. Te downtowns are shaded, and the upkeep has been done by professionals." Unlike cities that have steadily maintained their tree canopies, Pittsburgh is an example of a community that has begun to turn things around. Te city has estimated that for every $1 spent on street trees, it has received almost $3 in benefts — a value that has helped spur aggressive treeplanting campaigns. O'Bryan says that with the right structure, we can not only get more trees downtown, but save more trees from being removed elsewhere. How did we, a city that prides itself on its parks and parkways, let things get this bad? A combination of factors exists. For one, we were hit with huge wind storms in September 2008 and August 2011 and a massive ice storm in January 2009, all uprooting big trees and damaging branches. "Just looking at Tyler Park when I drive by — they lost a ton of full, mature trees, and it takes 100 years to grow those things again," Piuma says. O'Bryan says he thinks that natural disasters leave people feeling that trees are a nuisance and expensive to take care of, so trees often aren't replaced. "It's a cyclical thing where we think we have a lot of trees. It swindles us," he says. "We've been practicing for a long time not caring for trees." Tree management is not a new struggle among urban areas. In Te City in Mind, author James Howard Kunstler says that in 19th-century Paris, "greenery had to be a disciplined part of the urban order." Look at old sketches in local author John Findling's Louisville Postcard History Series and you'll see that the town didn't seem to have given downtown street trees much thought. Cities across the U.S. now realize the unfavorable efects of urban development and have worked to not only plant but also to preserve. New York, Philadelphia and Los Angeles each have goals to plant a million trees throughout the next decade. Louisville's sustainability plan aims to have a hundredth of that — 10,000 new trees — planted by 2018, with alleviating the heat island being the main intention. Some laws work to protect trees from a service standpoint. In Maryland, only licensed tree experts can perform tree services, cutting out a lot of the black market that frustrates O'Bryan. Another way to protect trees is through ordinances. Washington, D.C., requires a special tree removal permit for any tree larger than 55 branch of tree service is volunteer-run, which Piuma says has been the main tree-tracking method. Petry serves on a subcommittee of the Tree Advisory Commission, which is also comprised of volunteers. "Advisory being the key word. It's like a dog with no teeth," he says of the commission's lack of power. O'Bryan says he and his crew are also working to start a community tree-planting program, in which residents can request trees, donate their time to help plant, and the tree experts will help keep the trees alive and educate the homeowners on tree care. Even though we may lack some of these structural elements, Piuma says, based on his observations there are more trees downtown now than there were three years ago. Still, he says, we have a long way to go. Before taking summer break in late June, the Metro Council voted on July's annual budget. Included were funds for an urban forester, a countywide tree-canopy study and the planting of more trees. Metro Council President Jim King says the tree provisions were funded "to acknowledge the importance of maintaining and building our tree canopy in concert with the critical work of the Tree "It's a cyclical thing where we think we have a lot of trees. It swindles us. We've been practicing for a long time not caring for trees," says Chris O'Bryan. inches in circumference on public or private property. Louisville does have an ordinance requiring a permit for tree removal on public rights-of-way, but the measure does not extend to private property. Te exceptions to this are suburban cities such as Anchorage, Middletown and Prospect. Metro Louisville's landscape architect, Sherie Long, says, "In Anchorage, you can't touch a tree without a permit, even on private property." She says that Louisville's land development code does not currently protect trees as much as it could. "If you have a 100 percent tree site and you come develop it, there's nothing in the land development code that makes you mitigate the loss," she says. Te code states that on a formerly tree-flled site, the minimum developers are required to replace is 30 percent. "And that 30 percent is based on putting a stick in the ground and waiting 30 years for it to have any impact," Long says. "An ordinance would go a long way. It could talk about preservation; it could make special requirement for larger trees, maybe require some kind of compensation that developers have to pay if they remove certain trees." Apart from what businesses and the city can do, an undefned but much-needed Commission to inventory our trees and plan for ways to reduce our heat island." Te Ofce of Sustainability's Koetter says the city is still fne-tuning the forester's job description, but that he or she will implement the canopy study and act as a liaison between the arborist, the parks department and the community. Unlike the arborist, the forester will engage in a general, more comprehensive survey of the tree canopy. "We're looking for someone with technical expertise, with experience and education in horticulture and arboriculture," Koetter says. Even though changes in structure, ordinances, education and money are all needed to amplify the metro tree canopy and ease the heat problems we face, O'Bryan says that the most important thing is for us to do it correctly, which can be frustrating and time-consuming. We can pave potholes and enjoy the benefts immediately. Trees, living organisms that they are, require nurturing and often decades of maturing before we can hide under their leaves and catch a breeze. Trees are infnitely valuable, but they take a lot of work. Te Limbwalker crew, the Urban Design folks, the Climate Lab geeks, they might be making small steps every day, but it's these small steps that become good habits. 8.13 LOUISVILLE MAGAZINE 51